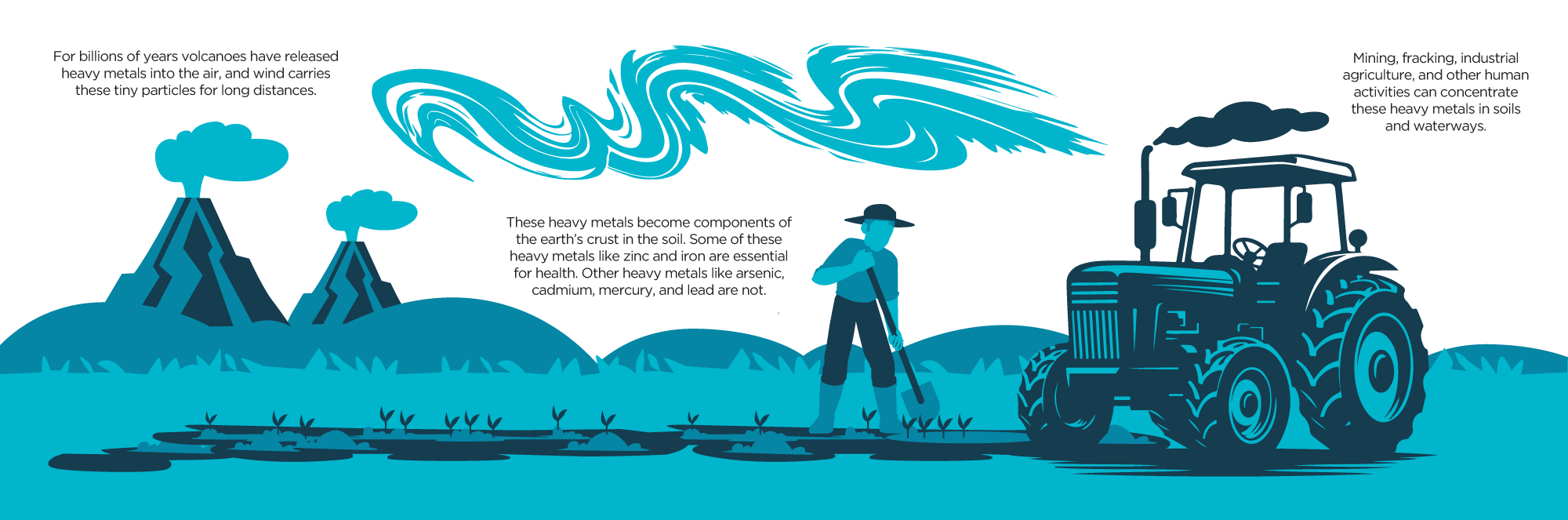

Heavy metals are naturally occurring elements found in the Earth’s crust, released into the environment through geological processes. Volcanic eruptions can propel these elements into the atmosphere, where wind carries their tiny particles over vast distances before they settle into soil or water. Dust storms further contribute, lifting and spreading these metals across regions.

Plants grown in such soil, absorb these metals alongside essential nutrients needed for growth and physical health. While naturally occurring heavy metal levels in soil are typically low and not a significant health risk, elevated concentrations can result in foods containing higher levels of these contaminants.

The effects of high levels of naturally occurring heavy metal exposure are often subtle, gradually accumulating in the body over time and silently interfering with vital bodily functions. While the damage may not be immediately visible, its long-term consequences can be severe, especially for children whose developing bodies are particularly vulnerable.

For instance, elevated lead exposure can disrupt brain development in children, leading to learning difficulties and behavioral problems. Excess mercury poses a serious threat to the nervous system, with severe cases causing tremors, memory loss, and worse. High arsenic exposure is associated with damage to the skin and lungs, as well as an increased risk of cancer, while elevated cadmium levels can harm the kidneys and weaken bones.

Recognizing these risks highlights the urgent need for proactive measures to reduce heavy metal exposure and safeguard public health, particularly for the most vulnerable populations.

Not all plants absorb heavy metals equally. Many fruits and vegetables have peels that act as a natural barrier, limiting heavy metal uptake into the edible parts. However, those with thin skins or those grown in contaminated soil may still contain trace amounts. Different plants also absorb heavy metals at varying rates. For instance, rice tends to accumulate arsenic, lettuce, and onions absorb lead more readily, and spinach and carrots are more prone to cadmium uptake from the soil.

Fish can also be a significant source of heavy metal exposure. Larger, predatory species such as tuna, swordfish, and king mackerel accumulate heavy metals through their diet. As smaller fish consume contaminated plants or animals, heavy metals become increasingly concentrated as they move up the food chain. Consequently, larger fish often contain much higher levels of heavy metals than the smaller fish they consume. Similarly, livestock raised on contaminated feed or grazing on polluted land may retain traces of heavy metals in their meat.

Human activities significantly contribute to heavy metal contamination in the environment. Mining operations, for example, extract heavy metals from the Earth, but improper handling or storage can release dust and waste that spread heavy metals into the air, soil, and water, contaminating areas far beyond the source. Historical practices have also left a legacy of contamination; lead from paint, gasoline, plumbing materials, and other products have entered the environment, and while its use has been largely phased out in the U.S., lead is still present in some products manufactured domestically and abroad.

Manufacturing and packaging methods also play a critical role in limiting heavy metal contamination in food. Certain processing equipment or packaging materials can leach metals into food, particularly acidic items like tomatoes or products stored for extended periods. In the past, heavy metals were components of inks, dyes, pigments, adhesives, and stabilizers used in packaging, which could migrate into the food they touched.

In attempts to cut costs, some producers may substitute or add ingredients that introduce heavy metals into food. For example, lead-based dyes have been used to enhance the color of spices such as chili powder, turmeric, and cumin, as color often influences perceived quality. These industrial dyes can pose severe health risks and highlight the importance of vigilance in food safety.

High levels of heavy metal contamination in food is a critical concern, requiring continuous efforts to minimize exposure and associated health risks. Manufacturers play a pivotal role by rigorously examining supply chains to limit heavy metal uptake in crops and animals. They can also adopt processing methods that avoid concentrating naturally occurring metals in food and collaborate with farmers and suppliers to source ingredients with lower baseline levels of contamination. Clean Label Project certification serves as a validation that these best practices are being followed.

However, it’s essential to recognize the limitations of completely eliminating heavy metals from our food system. These elements are naturally present in the environment and are absorbed and sometimes concentrated by plants and animals. While reducing exposure—especially for vulnerable populations like children—is vital, achieving absolute zero is neither practical nor necessarily beneficial.

Why? Striving for zero heavy metals could unintentionally lead to a food landscape dominated by highly processed products. Imagine a diet consisting mainly of items made with water, added sugars, isolated nutrients for fortification, and artificial flavors and colors. This shift could replace whole fruits, vegetables, and grains with processed alternatives, stripping away their rich array of known and yet-to-be-discovered health benefits.

The solution lies in balance. By prioritizing rigorous testing, vigilant oversight of producers and manufacturers, and ongoing innovation to reduce contamination, we can create a food system that safeguards public health without sacrificing the diversity and nutritional value of whole foods. This approach ensures that safety and nutrition go hand in hand, preserving the integrity of our food while protecting our most vulnerable consumers.

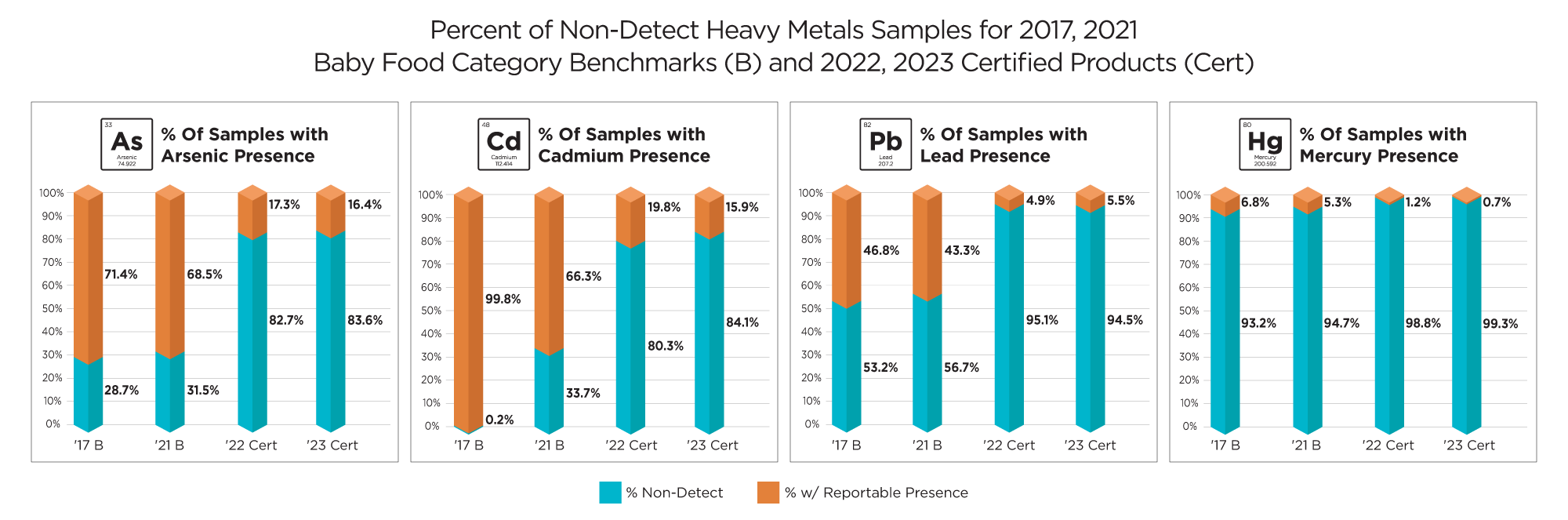

The Clean Label Project is leading the charge in transforming the baby food industry, pushing manufacturers to significantly reduce heavy metal content. Arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury—the metals targeted by both the Baby Food Safety Act, Closer to Zero, and California’s AB 899—are evaluated in the Clean Label Project Purity Award testing protocol. Through comprehensive market analyses in 2017 and 2021, Clean Label Project established critical benchmarks for the baby food category, revealing a substantial increase in non-detect (ND) results for all four heavy metals across the market across this time frame This is great news for infants, children, and public health revealing that regulatory action coupled with consumer advocacy efforts are meaningfully contributing to industry reform. Notably, the percentage of products with ND results for cadmium surged from less than 1% to an impressive 34%

The baby food category benchmark returned more non-detect (ND) test results in 2021 than in 2017, revealing a marked improvement in supply chain ingredient quality and purity. Clean Label Project certified baby food products also consistently return more non-detect (ND) results for heavy metals compared to the baby food category as a whole.

The data from Clean Label Project-certified products tell an even more compelling story. These products consistently outperform baby food category benchmarks, with a significantly higher proportion of ND results. This means the efforts made on behalf of certified brands to proactively and voluntarily opt into greater scrutiny in ingredient sourcing and testing has resulted in products with heavy metal concentrations that are closer to zero. In 2021, while 57% of baby food products on the market showed ND results for lead, 95% of Clean Label Project-certified products achieved ND status. This trend holds true across other metals as well: for arsenic, the market benchmark was 31.5% ND, while Clean Label Project-certified products achieved 83% for cadmium, the benchmark was 34% ND, whereas certified products reached 80%

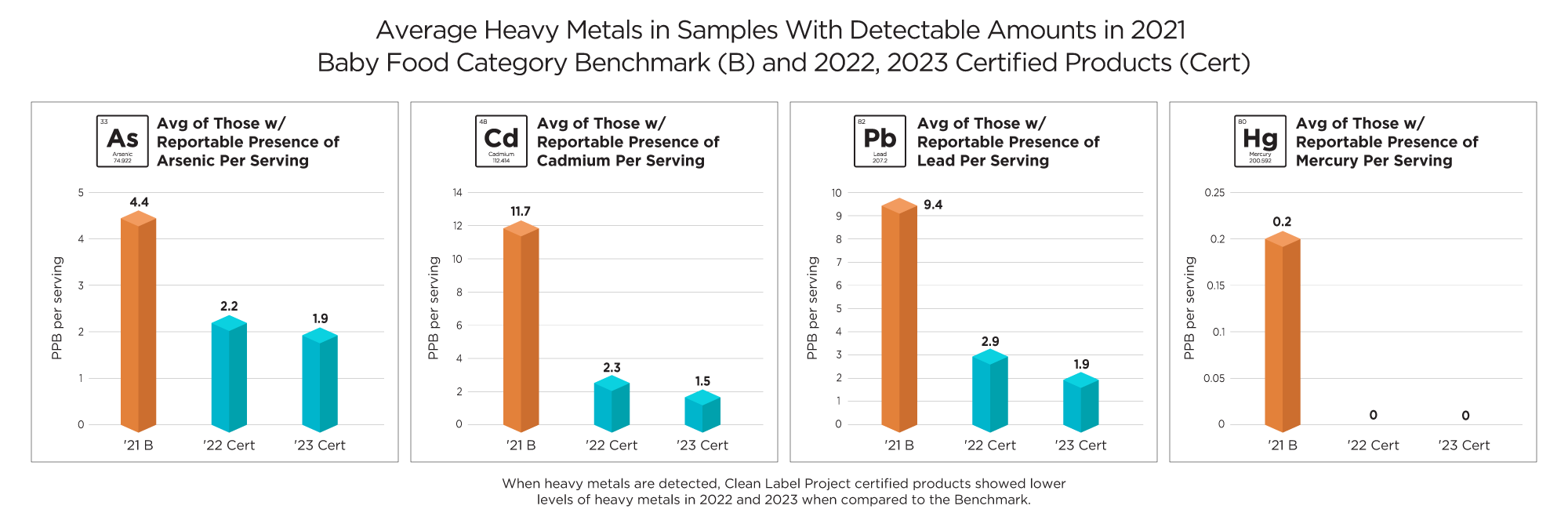

Moreover, Clean Label Project-certified products exhibit lower heavy metal levels even when detectable quantities are found. In 2021, the baby food category benchmark for cadmium and lead averaged 11.7 ppb and 9.4 ppb, respectively. By contrast, certified products, on average, showed lead levels of just 2.9 ppb in 2022, dropping to 1.9 ppb in 2023, a 34% reduction. Similarly, cadmium levels in certified products decreased from 2.23 ppb in 2022 to 1.5 ppb in 2023, a 33% reduction. Coupled with consumer advocacy and regulatory action, this consistent progress demonstrates Clean Label Project’s role as a key driver in improving the safety of baby food products.